27 Aug Collection in action – Aston Martin DB3S

This month we indulge in a longer than usual feature tracing the history of one of Britain’s most charismatic sports racing cars, the Aston Martin DB3S, and getting behind the wheel of FMM’s Woods Trust example.

Without doubt, the DB3S is one of the highlights in Aston Martin’s sometimes turbulent 104-year history. Conceived and built 64 years ago during the company’s somewhat flamboyant guidance of David Brown, the elegant DB3S was a racing sports car that always punched above its weight. What it lacked in sheer horsepower and outright speed it more than made up for with balance and superb handling, but it never quite fulfilled the ambitions laid out for it. Nevertheless, today it is one of the most desirable sports racers in the classic car world, a joy to drive as everyone who has had the pleasure will attest. And it does have an intriguing history.

Introduced in 1953, the DB3S represented a triumph over adversity for Aston Martin. It was conceived in the wake of the unsuccessful DB3 that the company introduced in 1951. The DB3 was designed by Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, the noted Austrian engineer who, pre war, had designed the Auto Union Type D Grand Prix car. Von Eberhorst’s brief was to produce a car that would be quick enough to give the Aston Martin Lagonda’s straight-six (designed by W O Bentley) a chance of outright wins. He used the 99 kW 2,6-litre engine as used in the Aston Martin DB2 Vantage, and in May 1952 the cars finished second, third and fourth at Silverstone behind a Jaguar C-Type. But the engine was clearly not powerful enough so it was replaced with a 2 922 cm3 version delivering 122 kW.

A DNF at the British Empire trophy race was followed by a three-car entry for the sports car Monaco GP, one finishing seventh, one retiring and the other crashed. All three works cars failed to finish at the Le Mans 24-Hour, two retiring early on with mechanical problems and the other went out after an accident with two hours to go. Among some mediocre performances in club events, a 2,6 DB3 won the 9-Hour at Goodwood. In 1953, a DB3 placed second at the Sebring 12-Hour and finished fifth in the Mille Miglia, then the highest position ever reached by a British sports car in the Italian classic. But that was the overweight car’s last claim to fame as it was replaced by the DB3S.

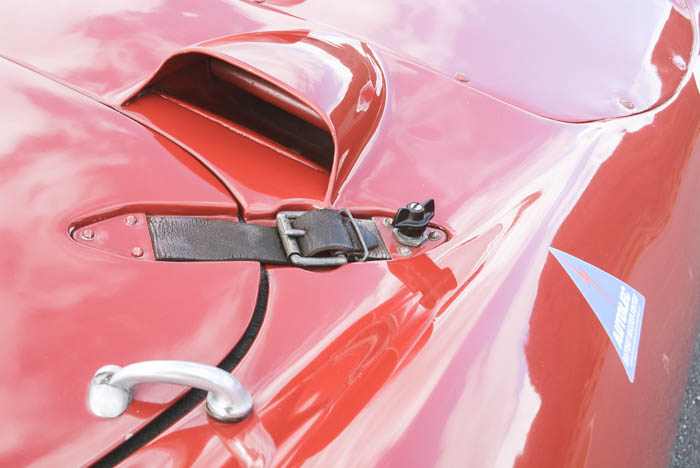

Concerned that the DB3 was proving to be ineffective, team engineer William Watson had offered a new design to Aston Martin’s competitions manager John Wyer. Watson had to be careful because he was employed as Von Eberhorst’s assistant and his proposal could damage Von Eberhorst’s pride. But Wyer saw the potential of Watson’s design that was shorter and narrower than the DB3 with a chassis incorporating a de Dion rear axle. Critically, weight was reduced thanks to the use of lighter chassis materials. And the smooth-contoured, low-slung bodywork produced by Frank Feeley certainly looked the part. Bigger valves and a modified camshaft helped increase engine power to 134 kW at 5 500 r/min.

Initially, though, the omens were mixed. A debut win in a minor race at the Charterhall circuit in Scotland prefixed a full works team entry at the 1953 Le Mans. One car spun on oil and crashed, the other two retired – a result that was to become all too familiar. But then fortune favoured the brave; the DB3S won every other event it entered during the year, including the British Empire Trophy, the Goodwood 9-Hour and the Tourist Trophy. As a result, Aston Martin finished third in the World Sportscar Championship (WSC).

In 1954, the troublesome inboard-mounted rear brakes inherited from the DB3 were transferred to the hubs, the only major change made to the chassis during the car’s lifetime. Engine output was increased to 143 kW, but the DB3S was still down on power compared with its rivals. Wyer wanted to win the WSC and the year started with a third in the Buenos Aires 1000 km, but brake failure eliminated all three cars from the Sebring 12-Hour. Accidents put out the works cars in the Mille Miglia while both were in the top six. The DB3Ss scored a 1-2-3 in their class at Silverstone, where the company raced the Lagonda V12 for the first time. The Lagonda, which was essentially a slightly bigger DB3S with the 4 486 cm3 227 kW V12 fitted to provide the power and speed that the Aston lacked, finished fifth. Later in the month, Carroll Shelby finished second in his semi-works DB3S at a new circuit, Aintree.

Le Mans was a disaster – again. Of three DB3Ss, two were fitted with a twin-plug head first used at Silverstone and power was raised to 168 kW at 6 000 r/min. The third car was run by Shelby in America’s white and blue racing livery. AML also entered a Lagonda and an experimental supercharged DB3S. None finished, the blown DB3S being the last to drop out after 21 hours. Fifth place in a race at Monza followed, then the team scored a 1-2-3 overall in the Sportscar race supporting the British GP, although opposition was weak. Thirteenth was the best finish in the Tourist Trophy.

At the London Motor Show in October, the DB3S was released as a production model with a motor producing 134 kW at 5 500 r/min, later increased to 157 kW at 6 000.

For 1955, engine bore of the works cars was increased and the capacity raised to 2 992 cm3 resulting in 182 kW at 6 000 r/min. Girling front disc brakes were also introduced to some works cars. The season began with a third in the British Empire Trophy handicap, a single-car DNF in the Mille Miglia, and a win at Silverstone followed by victory at Spa. A trio of Australian entered cars scored a 2-3-4 at the Hyères 12-Hour. Peter Collins/Paul Frère finished second in the ill-fated Le Mans 24-Hour. A seventh at the Swedish GP was followed by a first and third in the revived Goodwood 9-Hour. Then came a 1-3-8 finish in the 354 km Daily Herald Trophy race at Oulton Park, and a fourth and seventh in the Tourist Trophy behind a 1-2-3 by the dominant Mercedes-Benz 300SLRs, helping the team to finish fifth in the WSC.

Changes for the 1956 season included the adoption of dry-sump lubrication, which led to the nose of the car being made more streamlined to reduce frontal area, and an aerodynamic headrest was added. A fourth overall and class win at Sebring was followed by a win at Goodwood with newcomer to the team Stirling Moss at the wheel. After a win at Aintree, DB3Ss were first and second at the accident-marred Daily Express International Trophy. Into Europe, there was a fifth at the Nürburgring 1000 km then a 2-4-5 at the Rouen GP before a second at Le Mans. Back to Britain and a 1-2-3-4 finish at a rain-soaked International Trophy at Oulton Park before a season-ending win at Goodwood.

But the DB3S was proving less competitive, and with the Lagonda having been dropped without ever being on the pace, Wyer was busy developing the DBR1 as the company’s new challenger, and in 1957 it became the focus of attention. However, there was a swan song for the DB3S when brothers Peter and Graham Whitehead finished second in the 1958 Le Mans after all the works DBR1s failed to finish.

So the DB3S never fulfilled Wyer’s ultimate dream of winning the WSC, but it was not for want of trying. Apart from the already mentioned Collins, Frère, Shelby, Moss and the Whitehead brothers, Aston Martin’s other principle DB3S drivers were George Abecassis, the enigmatic Prince Birabongse of Siam, Tony Brooks, Pat Griffith, Reg Parnell, Dennis Poore, John Risely-Prichard, Roy Salvadori and Jim Walker. And Down Under, another ex-F1 champion, Jack Brabham, was one of the drivers at Hyères. All told a highly impressive and talented line-up.

Moss said of the car, “Although it was not as clean-looking as rival Jaguars, I always considered the DB3S one of the prettiest sports-racing cars of the 1950s. It was a forgiving car that you could throw around, although it had a habit of lifting the inside-rear wheel too easily when cornering really hard. As a result, you’d often ease off where other cars might sustain full throttle. But on a winding road circuit such as the Nürburgring or Oulton Park, it would out-handle a D-Type any time”.

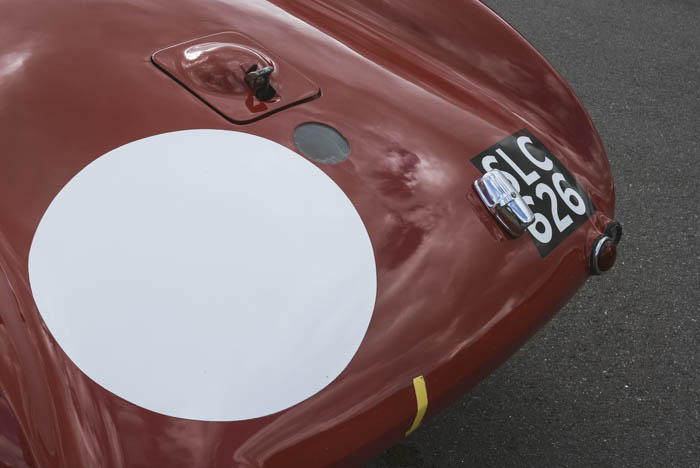

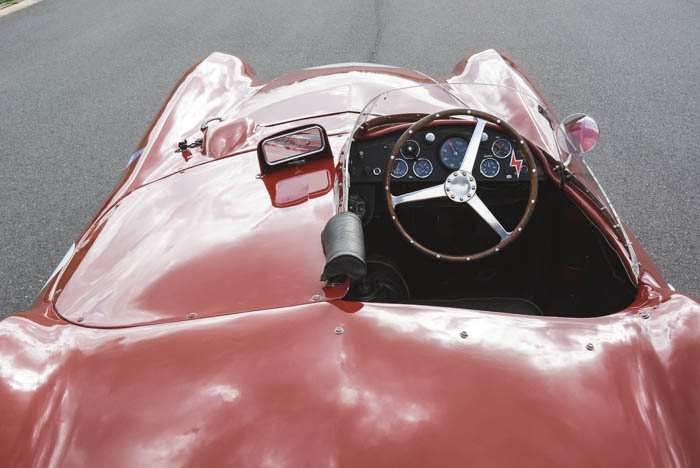

In total 31 cars were made, 11 works cars and the remainder sold for customer use. The Woods Trust car currently part of the FMM collection is one of the latter – chassis number DB3S/110 – that was built in 1955 but first registered on 17 March 1956. Its early history is not known until it appeared at a club race at Silverstone in 1975 after which it regularly appeared in historic race meetings in the UK. Originally fitted with the 134 kW customer engine, it has since been upgraded to the 157 kW spec. It is a joy to look at and I was surprised to find I could fit into the tight cockpit relatively comfortably. There is a special feeling sitting behind the wheel of a car like this, head exposed to the elements – the shallow windscreen wrapped around the driving position offers little protection. No fancy dashboard, just the necessary controls and instruments are offered. Once the engine has warmed up, the tonneau over the passenger space creates quite a hot tub effect inside, which was welcome on the sunny but cold day I drove the car.

The steering is nice and direct and without trying to emulate the heroics of the ’50s pilots, by keeping things smooth and tidy through the corners I soon got into an easy rhythm with the handling. Having had the pleasure of driving a Le Mans Jaguar D-Type, I soon understood a little of Moss’ comments. The four-speed gearbox snick-snicks with mechanical ease, and the bellow from the exhaust exiting just aft of the driver’s door rises in tune with the progressive throttle response, noticeably so once past 4 000 r/min. When called upon, the disc/drum brakes prove adequate. With trailing links and triangulated upper arms and torsion bars up front, and twin parallel trailing arms and transverse torsion bars supporting the De Dion axle, the ride is firm but not harsh. Dunlop Racing 6.00L-16s tyres are mounted on Borrani wire-spoke rims with knock-off hubcaps.

It is a car that the more you drive, the greater is the desire to keep driving, braking a little later, drifting a bit longer, accelerating a little harder, exponentially increasing the grin factor. Top speed is given as 220 km/h while 0-100 km/h takes around seven seconds. But figures alone cannot convey the satisfaction derived from driving a DB3S.