30 Mar Collection In Action: 1909 Le Zèbre Type A

Mike Monk reveals the story behind a small French car named after an African equid but soon lost its stripes…

Among the automotive world’s pioneering countries, France was in the forefront of burgeoning manufacturers, one of which was Le Zèbre. The two men who founded the company in October 1909 were Julius Solomon and Jacques Bizet. Solomon was a young graduate of the School of Commerce and Industry in Bordeaux, and began his career at Rouart Brothers, who were engine makers. Bizet, the son of famed composer Georges, was a car dealer and is said to have provided financial backing to the business. They met while both were working for Georges Richard, a French racing driver and automobile industry pioneer.

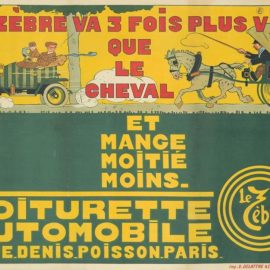

The name, unsurprisingly, means zebra, but why a French company would name itself after an African equid (a member of the horse family) is a surprise. According to the make’s historian Philip Schram, the reason is that Solomon and Bizet opted to not give their names to the car as was the usual practice of the time. Instead, they adopted the nickname of a clerk who they worked with while at Unic. Now why he was called Le Zèbre is not known…

The first, the Type A, was a light car built on a chassis supplied by S.U.P. who also provided the engine, the exact capacity of which is in some doubt as it is variously given as 530, 603 and 616cc. Power rating was 5 hp (3,7 kW) at 1 200 r/min. Front-mounted, the water-cooled single-cylinder vertical engine was mated with a two-speed gearbox with shaft drive to the rear wheels. In 1912, the engine size was increased to 645cc – raising power to 6 hp (4,5 kW) – and a third ratio added to the gearbox.

Records state that the first 50 Type As were built by Société Anonyme des Automobiles Unic, a company started in 1905 by Georges Richard, before Le Zèbre established its own facility in Puteaux, a commune in the heart of the Hauts-de-Seine department in the western suburbs of Paris. Selling for Ff3 000, the car was cheaper than its competition and was a sales success, staying in production until 1917, by which time 1 772 had been sold.

I approached driving FMM’s 1909 model with a sense of wonderment, and just looking at its petite stance – its wheelbase is 1 803 mm, which is shorter than I am tall – gave me a slight feeling of apprehension. So simple yet somehow elegant, the Le Zèbre shone in the hot summer sun, its gleaming red paintwork and abundance of brass fittings sparkling in the brightness of the day. Stepping up onto the winged and button-tufted leather dual seat merely heightened the prospect, the remarkably small thick-rim wooden steering wheel superb to hold. Once the oil feed and fuel supply had been primed, a half-turn of the starting handle was enough to bring the single-pot engine into life.

Another surprise was to find the pedal layout to be as we know it today, but the accelerator is bent slightly off to the right, close to the edge of the floorboard, which was going to require care once on the move. At this point, the purpose of a fourth ‘pedal’, rigidly fixed to the floor above and to the left of the accelerator, was unclear…

According to this car’s engine plate, the naturally-aspirated vertical engine is the early 5 hp unit, yet the gearbox is a three-speed, first introduced with the 6 hp motor, so how this pairing came about is something of a mystery. Gears are selected by an outboard lever working through a straight, notched gate that, on this car, had understandably become a bit loose after well over a century of use. But once a slight jerk indicated engagement, the Le Zèbre pulls away with more zest than the single-digit horsepower rating suggests. First is naturally low, but once on the move, gentle shoves on the lever brings the two other gears into action and the car surges forward with new-found strength.

It is light – kerb weight is given as a mere 350 kg – and top speed was said to be 30 mph (48 km/h), which in context is quite a heady velocity. Soft, all-round semi-elliptic springs provide a comfortable ride and the steering is direct and far from heavy, riding on 26×3-inch tyres mounted on artillery wheels. The mechanical rear drum brakes do their job without having to apply excessive force.

Once settled into top gear, phut-phutting along leaving a faint trail of smoke in its wake, driving the Le Zèbre proved to be a real joy. Care had to be taken to not knock the gear lever out of position as the lever provides a natural rest for the right leg as a result of the accelerator position. Incidentally, the car still has a leather clutch. That fourth pedal? Back at the workshop discussing the drive, workshop technician Donny Tarentaal had a light bulb moment: placing the ball of the foot on the fixed pedal, you can operate the accelerator with your heel. Not exactly instinctive, but the prospect puts a fresh take on heeling ’n toeing…

And to clear up another oddity, the brass badge on the radiator has caused some confusion. The stylised wording says simply ‘Zebra’. When compared with the company’s official badge, the ‘Le’ is missing, and the name should be Zèbre not Zèbra – oddly though, on close inspection, there does appear to be an accent over the ‘e’. But some cars were sold in England under the name Zebra, and badged accordingly. A famous AC dealer in London, F B Goodchild Ltd, was the UK agent from, apparently, 1914, so it is fair to assume this car was imported from England with its Runabout body and must be a rare remaining example badged as a Zebra. Its registration number, A2180, is original and confirms the car being first registered in London.

Coincident with the Type A’s mechanical upgrade, at the 1912 Paris Salon the company introduced two four-cylinder models, a 1742cc Type B and a 785cc Type C, both with V-shaped radiators rather than the A’s flat grille. More than 1 000 Le Zèbres were sold that year. During WWI, while Le Zèbre was supplying 40 cars per month along with various military parts to the Ministry of War, Solomon helped design a four-cylinder Citroën for Andrè Citroën, who was then working for Mors. In July 1917, Solomon joined his compatriot full-time, and two years later Citroën was founded as a motor manufacturer in its own right.

After the war, Le Zèbre became an endangered species as market leadership was quickly diminished as the demand for cheap small cars rose rapidly, leading to the creation of a plethora of other manufacturers keen to get in on the act. Peacetime production began with a four-cylinder 997cc Type D, followed in 1920, in answer to public demand, with the 4 hp Monocylindrique, but this was short-lived, as were the subsequent Type E (a sportier Type D) and a 10 hp version of the 1923 Type E Amilcar made under licence. Desperate to improve sales, in 1924 the Type C/Armée appeared to compete with the 5CV Citroën but failed dismally, along with the Type Z with its 1973cc four-cylinder engine boasting Harry Ricardo’s patented hemispherical combustion chambers cylinder head. A single-cylinder, opposed-piston, two-stroke diesel-engined model was shown at the 1931 Paris Salon, but later in the year the factory was forced to close.

And so Le Zèbre became extinct, but FMM’s survivor is now on view in Hall B.